The only way a collector of prints made by an individual artist can really know what they are doing is to have a catalogue if their work. Even now, very few of the colour print artists who have featured on Modern Printmakers have anything like an adequate catalogue but they do exist, both in the United States and the U.K. Notable among them are the catalogues put together in Britain by James Trollope for Arthur Rigden Read and Eric Slater. There are also well-produced hardback catalogues for the prints of Norma Bassett Hall, Edna Boies Hopkins, Walter Phillips and Sydney Lee. Then there are further catalogues for three artists associated with the Grosvenor School, namely Claude Flight, Cyril Power and Sybil Andrews. Finally, there is the compendious catalogue for Yoshijiro Urushibara and the meticulous catalogue for John Platt produced by Hilary Chapman.

As a curator at the V&A once warned me, it can take years to put together proper catalogues like these and while this is true, a working document of some sort can also also very useful. For example, I know of check lists for Mabel Royds, Ian Cheyne, Helen Stevenson and Kenneth Broad put together by individuals or by two people working together (as I did with Broad's grandson). The print catalogue for S.G. Boxsius is ongoing and The black bull (featured at the top) tells you why. The image was sent to me by a reader only quite recently. Not only had I never seen it before, I had never even heard of it simply because there is no exhibition record for it - at least not that I know of.

Boxsius often tried to create mood in his prints one way or another. The black bull was not the only occasion he attempted to catch the fleeting effect of sunshine and rain that is typical of Britain, specially near the coast. Corfe Castle is one print people will know. There is also Rain, St, Michael's Mount where his attempt to depict falling rain tends to spoil what is otherwise a beautifully made print. With The black bull he decided on a more stylised effect and although the rays remind me of the sunburst on my grandmother's 1930s drive-way gate, it does ring true to the period and without doubt he gets away with it.

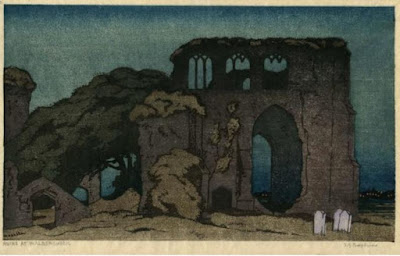

Another print that I came across only this year was his linocut Ruins at Walberswick (above) which I have talked about in a previous post. All this only goes to show that there are almost certainly others which are in private or public collections like these two. As institutions like the University of Wales and the National Gallery of Scotland put more of their collections online, we are gradually getting a better idea of the range of work [produced by artists like Boxsius. But it is the same for Modern Printmakers. As readers send in images that are new, the more we get an idea of just how many prints he made. In all, I have records for forty colour woodcuts or colour linocuts and most of these I can match up with images. There are a few like Wind and Pines that may be hiding somewhere. It is hard to say but I tend to think there are other prints by Boxsius still out there. One reason I say this is because after his death, his wife, Daisy, kept much of his preparatory work which was then inherited by members of her family. It has always been believed there was a studio sale at some stage after Boxsius' death. Whatever happened, the watercolour designs and sketchbooks that survive are exceptional not only in their quality but by the very fact that they have survived at all. No one that I know of except for Mable Royds left so much studio material behind them and this makes the preparation of a Boxsius catalogue as rewarding as it is demanding.

At least one preparatory drawing I have seen matches the linocut Twilight at Winchelsea. It shows Boxsius making meticulous drawings he then transposed to wood or lino. Alongside many of the designs, he there are colour charts with notes. Unfortunately, the images I was sent are not square but I have decided to post one of the drawings which looks to me like a design for a linocut. This should give readers a better idea of the way the artist worked and may encourage people to send in other images. There is no colour chart beside this one, but it is the best image I have and the best example of the careful planning Boxsius undertook before cutting the block.

There are two problems when it comes to putting together any kind of Boxsius catalogue. Firstly, no one has any real idea when he began making colour prints. He may have begun as early as 1899 to 1900 when he was a student at the Royal College of Art. William Giles was probably teaching there at the time and published his first colour woodcut in 1900. A number of Boxsius prints owe a debt to Giles and in 1926 he wrote an article about linocut for Giles' Colour Print Magazine. Obviously this means that Giles must have known his linocuts by then. Boxsius certainly knew Ethel Spower's The green bridge (above) also from 1926 and made after a visit to Walberswick. The fact that both artists worked at Walberswick is too much of a coincidence and the figure on the bridge could be Daisy Boxsius taking a break from making watercolours. After all Boxsius placed what looks the same woman on the same bridge!

But as you all know by now matters are never straightforward when it comes to Boxsius. Another artist who depicted the Kissing Bridge was Sydney Lee and the other possibility is that Boxsius took Lee's colour woodcut class at the Central School some time after 1906. Boxsius owed more to Lee than he did to Giles. You only need to compare Lee's Drying sails, St. Ives (above) to the drawing by Boxsius below to appreciate the way Boxsius used the work of other artists as a starting-point. It is not the same but they are similar in scale though Boxsius' figures are greater style and charm than Lee's. So far as I know no-one was using lino in Britain at the time Lee was running his colour woodcut and wood-engraving class in London but Boxsius must have been making them soon after the end of the first war. There is nothing exceptional about that. What is unusual is the way he used both wood and lino. Most artists who did used both were like Isabel de B. Lockyer, Anna Findlay or Spowers who all used wood before adopting lino from the early to mid twenties onwards. Boxsius first exhibition date is for the linocut Rain, St. Michael's Mount in 1928 when he was already fifty years old.

This leads us to the other problem anyone would be faced with when putting together a Boxsius catalogue: how does anyone date the prints? None of them are dated and the exhibition record is patchy considering we now know of forty prints. It may be the first record we have for him, but Rain, St. Michael's Mount is obviously not an early work. But then how many obviously early prints are there? To my mind, there is only Old mill, Sussex. All the rest are the work of an experienced printmaker which can only mean that Boxsius had been more concerned with teaching others how to make prints rather producing professional work himself. It also suggests that making prints for exhibition should be classified as the special achievement of a mature artist in line with, say, the superb results gained by Arabella Rankin when she began making colour woodcuts at the age of fifty or Mabel Royds great flowers prints made during the last ten years of her life. All three of them were class performers and prove how far maturity can win out for artists who are determined and have the nerve to break loose.