The Grosvenor School is the sort of place where you would like to walk to Warwick Square, wander in and speak to Miss Andrews in the office, to enquire whether you could look in on Mr Flight's class so you find out just what they were all up to. I suspect it was the kind of place that had as much in common with the community of artist-converts at Ditchling in Sussex as it did with the Bauhaus in Weimar, Germany. Claude Flight (1881 - 1955) was a linocut evangelist and everyone, including the staff, attended his classes. It's no wonder they all made so many.

It was set up in this rambling old house in 1925 by three men who had all come to art and print later rather than sooner. Flight had tried out various things, including bee-keeping, untill he hit on modernism and, in particular linocut, as the answer. As you see from his

Swiss Mountains from c1934, he was an enthusiast. He had begun making linocuts in 1919 and taught students to use separate blocks for each colour. In 1929 he organised 'The first exhibition of British linocuts' and even if his name is almost synonymous with linocut today, his enthusiasm for the Grosvenor School was short-lived. He taught there for only four years, from 1926 untill 1930, when he transferred his already informal classes to a cave above the river Seine.

Flight had studied at Heatherley's School of Fine Art in London both before the war and then after. Cyril Power (1872 - 1951) didn't enrol at Heatherley's untill 1925 when he was already 53. He had been a successful architect but turned his mind to art. He had met Sybil Andrews in 1921 and she duly became school secretary. (See Sybil Andrews: the rural year, February, 2011). It's not hard to see his interest in both architectural design and form in general in

The Tube staircase, 1929. It shows the stairs at Russell Square underground station in London, an exact location for a dynamic print. If their modernism is at times far-fetched, this linocut does put me in mind of Marcel Duchamp.

Power gaves classes on architecture and ornament (he had already published a three-volume book) but the only one of the trio with any prior experience of teaching at all was Iain MacNab (1890 - 1967) - and that wasn't much. If I also tell you he spent a year at Glasgow School of Art in 1917 before also moving to Heatherley's in 1918, you will begin to see the pattern. The brave idea of a school dedicated to modern art may well have begun with their joint experience of a London private art school. (I'm not suggesting the experience was bad because MacNab became joint-principal of Heatherley's in 1919 and didn't relenquish his post of director of art studies untill as late as 1953.) But in 1925, even with his limited experience, MacNab took on the job of principal at the Grosvenor and certainly stuck at it longer than Flight.

MacNab was also one of the finest British wood-engravers of C20th. The effect of prints like

Corsican Landscape on his students of wood-engraving is clear; it may be less obvious with the students that practised other forms of printmaking but it there nevetheless. As for the students themeselves, I started the post off with

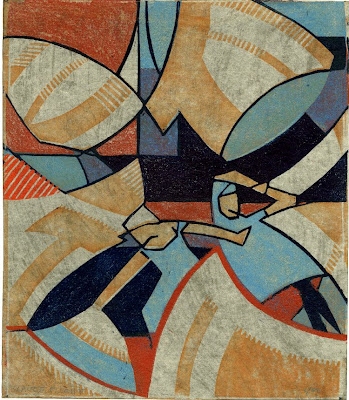

French Porters by the most talented one them all, the Swiss printmaker, Lill Tschudi (1911 - 2004). She came across the linocuts of that albatross-around-my-neck, Norbertine von Bresslern Roth, while still at school in Switzerland. She saw the school adverts in The Studio and attended between 1929 and 1930 when Flight was still teaching there. Like some of the other students she also trained with the French cubist Andre Lhote. It wasn't a matter of this being their only brush with modernism; some the students could obviously afford to pick and choose.

The Australian artist, Ethel Spowers (1890 - 1947) was one. She had studied art in Melbourne then moved to Europe in 1921 and, just to let you know what their first prints could be like, I include Spowers woodcut

Eglise de Grace, Paris made during her first year in Europe. As you see, it isn't up to very much at all.

Tug of War she produced in 1933, after her return to Australia, and is a fine piece of work without having the modernist thoroughness of Tschudi. Spowers only spent part of 1929 at the Grosvenor but it had a great effect. Linocuts she produced before that time were stronger than her early woodcut effort but conventional untill Claude Flight showed her how.

Eveline Syme had been at school with Spowers in Melbourne but went on to study classics at Cambridge. She turned her mind to painting and France in the early twenties but it was the discovery of Flight's book

Lino-Cut that led Syme and her friend Ethel Spowers to enrol at Pimlico in 1929. I like the way they all went back home and turned the technique on Australia. It has of course helped to make their name. But that process only began in the 1970s, with the vogue for all things Deco. Nowadays a dealer on ebay only has to add the illustrious words 'Grosvenor School' to some linocut or other to prove that linocuts will never be affordable or democratic again. The

idea had been to show the modern age they lived in - what everyone else was doing when they were making linocuts - in a modern way.

Wattle tree is by Dorrit Black (1891 - 1951). I think she is the weakest of the three Australian artists but this does show what they were about. She studied in Melbourne before heading for London in 1927 when she spent a mere three months at the Grosvenor School. It wasn't long but it was clearly enough. The British artist Gwenda Morgan (1908 - 1991) studied there far longer - between 1930 and 1936. This almost certainly couldn't have been a full-time arrangement. She had already spoent the years 1926 to 1929 across the river Thames at Goldsmith's, after all. But the example MacNab gave shines through much of her fine body of work. These wood-engravings may not be as thrilling as those linocuts but her work stays in the mind a long time after excitements have washed over it.

Ronald Grierson (1901 - 1992) was another student of MacNab's. Mainly known as a designer of textiles, he had also first studied elsewhere (at Hammersmith School of Art) before spending time at the Grosvenor. Alison MacKenzie (1907 - 1982) didn't arrive untill the 1930s (with her sister Winifred, see July, 2011). Both had studied woodcut with MacNab's sister, Chica, at Glasgow School of Art. It was a small, quite short-lived world for many of them, I imagine, far from the formal disciplines of many art schools and more in line with the progressive independent schools that were being opened up - but far more dependent than they were on the trends.