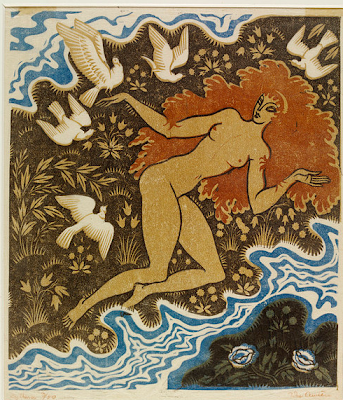

The British artist, John Austen (1886 - 1948) is best known as a prolific illustrator of books throughout the 1920s and 1930s, but he also made a small number of wood-engravings and some striking decorative linocuts like Cythera (above), which provides the necessary contrast to the prints I had a look at in the last post. If Flight's early linocuts are twenties bohemia through and through, then Austen's, which date from about 1930 on, are thirties to the core.

He was the son of a carpenter at Buckland near Dover, but decided against following in dad's footsteps and took the road to London instead, to train as an artist. Where, I do not know, but by the time he was twenty-five he was living in Eltham in south-west London working as a designer and illustrator for a correspondence course. (Interestingly enough, EA Verpilleux was doing something similar at the time in west London). He married Ruby Thompson when he was thirty-three, and I am told that Thommy provided the model for this beautifully polished pen-and-wash, as she did for many other figure-subjects. Years before, Henry Tonks at the Slade School had asked his students to spend less time looking at The Yellow Book and more time in the National Gallery. Looking at the way he had both Italian quattrocento and 1890s draughtsmanship off to a T, I think Austen must have done both.

Everywhere he went, he seemed to absorb the styles of others like the proverbial sponge. He is the classic imitator who originates. Quite alot has been said about the influence of Aubrey Beardsley in his early work. This may partly be because the illustrations for Hamlet, and similar work, are what people like and know. But there is more to him than that. The masks he used have a formal rectitude Beardsley wouldn't have been bothered with. What he really learned from Beardsley wasn't so much the decadent manner as it was to make the human figure central to the design.The well-lit skull wouldn't be out of place in a contemporary fantasy comic. It might be dead, but it is modern.

What appeals to him almost everywhere he goes is classical art. Sometimes the approach is direct, sometimes the approach is by way of the C18th. While some contemporaries like Ronald Grierson attached classical odds and sods to their linocuts, Austen tries and explores the world they come from. I specially like this wood-engraving made for Aristophanes The Frogs in 1937. Its roots are in the work of Thomas Sturge Moore, who he would have known as a contemporary of Beardsley but its workmanship and sense of authenticity are modern as well.

,

He is always professional, adapting styles and techniques, but always to the back of him is a rigourous training and an an eye for the formal qualities of art. The female figure is also a major theme. Even when he depicts Sir Galahad, the unmistakeable features of his wife appear above the suit of armour. Hamlet's large eyes and little chin must belong to her as well. But the one I couldn't resist posting is the witty interlude below.

His interest in the details go hand in hand with his sense of authenticity. For instance, the perm is quite sensational but are nothing compared with the headlamp eyes. The boundary between observation and imagination is as fine here as it is with many of contemporaries. Like Edward Bawden and Edward Ravilious, he trawled backwards in time, picking up the styles he needed. What surprises me is that he could make such a good linocut as Cythera and still not be known for work like that. Quite simply the editions weren't big enough. (I also want to add that professional photography doesn't always do linocuts like this justice. The camera and the lighting fail to pick up the hand-made feel that makes them exciting and human.)

We don't really know enough about his career to say why he failed to make more prints but he left London after an illness in the late twenties, I think, and the couple went to live at various rural spots in Kent that included an oast-house. These are the kinds of details we have. In the last years of his life he shared poor health with his mentor, Aubrey Beardsley. Unable to work, he was placed on the Civil Pension List and died at 62. I don't have a very good image of the messenger-god, Hermes but I wanted to include another print. It's probably Thommy again in disguise, anyway.

Finally, there are two sites I have to acknowledge as very useful sources: firstly, Jim Vadeboncoeur's 'Illustrators' based at Palo Alto, and then Brian Austen's 'Austen Families' at Hobart.

Thanks also to Keith (aka grumpyangler) for additional biographical info.

No comments:

Post a Comment