The to-and-fro of printmakers between New Zealand, Australia and Britain is fairly well-known now but even with an artist as popular as John Hall Thorpe many of the details that make the story worth telling often remain largely absent. Thorpe, of course, was in the self-promotion business and we have to take quite alot of what he has to say about himself with a pinch of salt. The linocut contingent who came to Europe and studied at the Grosvenor School in London now have their reputations dominated by those few months spent working with Claude Flight for a few hours every week. So far as I can make out, Helen Ogilvie didn't relish life in England and the second time she travelled to Europe, notably set up camp in Italy. The even smaller island of Capri suited her better.

How Ogilvie came to make colour woodcuts (see her post) is a blank. And I have only a bit more of an idea of the way Margaret Preston might have begun. Her first formal training was private lessons with William Lister Lister. He had gone off to Glasgow to train to be an engineer but had lately returned to Sydney as a fully-equipped artist. It was a common enough story for men at the time and by the time she was twenty-eight, Preston found herself travelling to study in Munich and Paris in the company of one of her own students, Bessie Davidson. That was between 1903 and 1905, seminal years to be in Paris to study art, and that's for sure.

And in 1912 she was back again in Paris, this time with student Gladys Reynell. The pair only moved on to England after the outbreak of war and even then it took another two years before Preston (and presumably Reynell) became students yet again, this time at Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts in south London. I don't know whether it was by chance or by design that this distinguished school was founded where the working-class districts south of the Thames turned almost rural (and had therefore attracted the likes of John Ruskin). But its philanthropical foundation and sense of practicality and outreach to working men and women made it a bastion of the English Arts and Crafts. (Its art gallery opened in the evenings and on a Sunday to allow working people to visit).

I assume that the potter, WB Dalton was still headmaster at the school when Preston studied there but in a way, it doesn't matter. He had been instrumental in getting the ceramics course started, Roger Fry had been a student, and this was one course Preston took, along with basketry. (We are now quite some way from Dufy, Picasso, and Matisse).

The National Gallery of Australia also suggest she took up printmaking here. Like many at the time, she gave etching a try and found it didn't suit her. For her, it was the equipment; for Walter Phillps, it was the mess and, even worse, the smell. She also gave colour woodcut a try. But all of the prints you see here are hand-coloured. Although quite a few of her colour woodcuts exist, I've never seen one anywhere. Significantly, she also had a crack at fabric-printing.

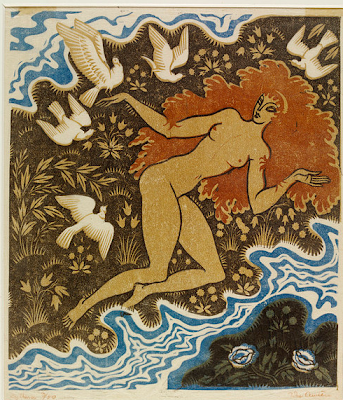

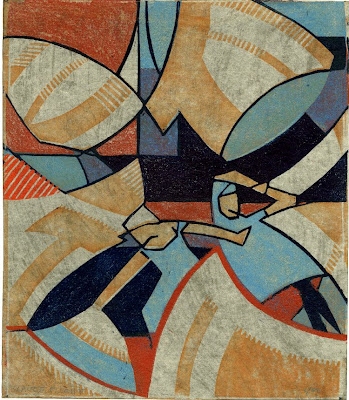

What the tale really is, I don't know, but it intrigues me, I have to admit. But there's something almost retrograde in all this. The facts from Australia are that she began making hand-coloured woodcuts in the early twenties and yet she harks back - to Gaugin, William Nicholson, the Fauves. And her attempts to make use of aboriginal art are irritating. But she went her own way. The earliest print here is Shell Cove, Sydney (third from the top) from 1920. By then, she was back in Australia, making prints and married. She was forty-five.

From then on, she became established. She exhibited with her friend, Thea Procotor, but her joint exhibition with Norbertine von Bresslern Roth and Frances Blair (see her post) at the Grosvenor Gallery in Sydney is one of the shows I imagine walking round. (The catalogue must still exist, surely). I suspect that if she didn't like all the equipment for etching, she would be not much keener on all the tackle she would need to make a colour woodcut. The point is that Australian claims for her as a printmaker are rather far-fetched. She has been roped in for the Japanese method and there is nothing remotely Japanese or method about her work. Not really. Nicholson broke new ground; Royds had the wit to take his example and print everything. Preston, I fear, took the easy way out.

.jpg)

+etching+Coats.jpg)

!~~60_12.jpg)