If The paper mill had been the only print Anna Findlay had ever made, it would still have a reputation as the one modern colour linocut that showed the way forward, even though no one followed, including Anna Findlay. She attended Glasgow School of Art and was a founder member of the Society of Artist Printers set up in Glasgow in 1921. Because their exhibition catalogues are few and far between it is hard to know what prints she was making at the time. All of them were colour woodcuts like the harbour scene (below). Her brother and his wife, Cecile, lived at St. Ives and Findlay spent time in Cornwall and exhibited with local societies but eventually moved back permanently to Glasgow so the harbour may be in Cornwall or in Scotland (and the houses suggest it is the latter).

Moving between Scotland and Cornwall was all very well. The fact was the British print scene was metropolitan and to make a mark you needed to be in London or nearby. Ethel Kirkpatrick worked in Devon and Cornwall for many years but her main home was always at Harrow on the Hill on the outskirts of London. All I have of Findlay's work from the early twenties are two black and white reproductions for a print catalogue. Apart from illustrations that appeared in The Studio Magazine, that is about all there is though everything I have on file is worth considering. You can see the viewpoint she adopted was the same as the one she later used for The papermill. In both prints we are looking across an enclosed area of water towards a group of buildings and even though the style is different, the sense of purpose is the same; she is well organised and offers narrow spaces to lead us in.

We are fortunate that two of Findlay's sketchbooks have survived. One of them contains the striking scraperboard image (above). I have tried without success to identify the paper mill and I cannot even be certain the scraperboard mill is the linocut mill but I think it is likely simply because one image is certainly in preparation for the other (or at least for a different print). It is the first real sign of the rigour Findlay applied as she made herself into a modern artist rather than a genre one. The scraperboard also infers she was experimenting with new mediums. It is often said that Findlay studied with Claude Flight at the Grosvenor School. I do not think this is true and moreover it implies she needed Flight to help her change. I am not saying The paper mill does not show the influence of Grosvenor style but by 1932 of his teaching at the Grosvenor but by 1932 when Findlay first exhibited the print, the linocut class was history (it ended in 1929) and Findlay's cool appraisal and sense of formal depth has little in common with the self-conscious verve and surface design typical of about every linocut made by an artist who worked with Flight. You could just not ignore him - or his approach!

What is perhaps worse about all this is the way the example set by Chica MacNab has been missed. Unlike Flight, she offered both woodcut and linocut training to her students. Beyond that, the faux naif genre style Findlay used for her early woodcuts owes a good deal to MacNab's example (though again we have very few examples to go on). In the end, we do not have all that much to go on, though the survival of the sketchbooks have at least made it possible to see say something about her working methods. As I said, it is now generally agreed The paper mill appeared in 1932 and was an immediate success. The Contemporary Art Society bought number two from the edition of fifty printed on cream paper (see top) and presented it to the British Museum in 1934. But by then, Findlay had already made some changes to the print. The first proof she signed (above) does not have the light reddish-brown on the central building and is cream and white. It is clearly marked 1/50 (below) but I do not offhand recall seeing it in the BM. But then I have never seen any of these proofs. I think 1/50 must have come up somewhere for auction otherwise I would not have the detail of the edition number you see below. Details are not what museums do.

The paper mill even made its mark in St. Ives when shown there in 1933. The Cornishman newspaper advised its readers that Findlay's 'meritorious sketches' would 'repay close scrutiny in 1929, and here conservative Cornwall appraising a modern artist for the first time (or so it would appear): 'There is some attractive work in non-traditional modes, but nothing clamorous. Miss Anna R Findlay has given the Japanese manner the impetus of her intensely personal vision. She show The paper mill, Le Treport and Railway Bridge, of which the first, a lino cut, is decidedly the best.

The praise of the modern style is not only generous it is also perceptive and no one would disagree ninety years later that The paper mill was 'decidedly the best' though with hindsight we could say it was decidedly one of the best of all British linocuts made during that hectic ten years between 1929 and 1938. The way Findlay herself took a second and a third look and made at least three versions of the print implies she was pleased but could not decide what exactly was 'decidedly the best'. Christchurch Art Gallery in New Zealand hold a proof inscribed in the margin and not within the image (above) that may be 19/50. This contains a further revision that suggests how modern Findlay's sensibility was. Rigorousness and self-criticism helped to make the 1930s what is was and in that respect she is closer to Ben Nicholson than she is to Flight. The gallery give an edition number that does not make any sense to me but we can assume their proof came from the Redfern Gallery some time in the early 1930s because their former director gave it to Christchurch in 1954. The Metropolitan Museum of Art own a fourth proof but do not illustrate it or give the edition number.

The paper mill was exhibited widely in the early thirties. It was chosen by Campbell Dodgson of the British Museum to go on tour as one of 100 prints bought by the CSA, with venues including Blackheath School of Art, the Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle and the City Art Gallery, Leeds. (It reached Blackheath in February, 1934). It also toured the West Country alongside a smaller number of modern linocuts early that year and presumably also toured with the Exhibition of British Linocuts.

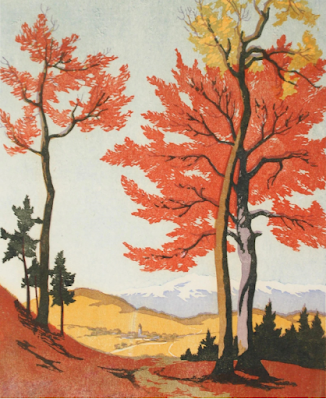

Is The paper mill a masterpiece in the way Ian Cheyne's Beeches at Glen Lyon is a masterpiece? Or does it stand out because it is unlike Findlay's other prints (Railway Bridge aside)? Contemporary judgements are often the best so it may be wise to acknowledge the praise given by The Cornishman. Frankly given the option of owning the Findlay or the Cheyne, I hesitated, but in the end I am sure The Cornishman was right.