Sunday, 23 October 2011

The studio in Liboc: Walther Klemm & Carl Thiemann

Of these two friends, the one to leave their home-town of Karlsbad first was Walther Klemm (1883 - 1957). Somewhere along the way, he met and made friends with the gregarious Prague artist Emil Orlik. One German sources says it was Orlik that encouraged Klemm to enrol at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Vienna; another believes that Klemm studied there between 1901 and 1904. Only one of these statements can be true because Orlik didn't return from Japan untill 1902. Nonetheless, Klemm certainly studied at the school of applied arts and in Kolo Moser he had a teacher who was the quintessential Secessionist designer, well-connected, stylish and urbane. And my hunch is that it was Moser that may have made the fateful introduction to Emil Orlik.

Orlik had barely established himself in Vienna than he had set sail for Japan. He stayed for eighteen months, training in printmakers workshops there. This was something completely new. He was the first European ever to study there and Klemm was fortunate enough to learn the techniques of woodcut making directly from him when he came home. The window of opportunity was relatively small; Orlik was not to keep up his interest in woodcut anymore than Klemm was. Ironically it was Carl Thiemman (1881 - 1966) who was to be the greatest beneficiary. And all this says a good deal about the kind of person Klemm was. Simultaneous with his studies at the Kunstgewerbeschule, he had taken classes in art history at the university. As I've said before, Klemm's prints appeal as much to the mind as they do to the eye. This keen interest in both the techniques and ideas that inform art shows what kind of an artist he was. I think he was attracted to ideas; you only need to compare these first two prints (Thiemman at the top, Klemm below) which were made probably less than a year apart, to see that really he was nothing at all like Carl Thiemann. A common birthplace and common interest brought them both together. Klemm made his first woodcuts while still a student in 1903 ie about a year after Orlik's return, and by 1904 was exhibiting with the established artists of the Vienna Secession. This was early success but all the same he left for Prague.

The connection may have been Orlik again. Although based in Vienna, he had kept on a studio in the city and by this point Thiemann was sutdying at the Academy. He had left Karlsbad where he had had to support his widowed mother and younger brothers and sisters while he worked in business, to study painting and etching but all this was rather sidelined by the arrival of Klemm. Some sources have them down as school friends. Klemm was now 23, two years younger than Thiemann himself, but with indirect access via Orlik to the great studios and workshops of Japan. Imagine the excitement of these two young men as they took on their own studio in the village of Liboc just outside Prague. They were to spend only four years there but in that time together they went on to produce some of the most sensitive and articulate prints of the period. The second irony is this: they were both young enough to take the lessons of the Secession to heart; Orlik probably was not. Just take one look at Thiemann's glorious cockeral to see what I mean. Orlik never displayed such bravura.

Nor, for that matter, did the hapless Klemm. By 1906, when he made his woodcut of two turkeys, he had developped his own style, straightforward subjects from the countryside around Liboc that were themselves subject to that analytical eye of his. The square, bold images of the Secession comes out into the fresh air. The canny Thiemann merely lifts the idea from his friend - the pair of birds, the trees connecting the high horizon to the keyblock - and turns it from interesting to irresistible. His woodcut is as opulent as Klimt but wisely dispenses with the self-absorption (and substitutes a sense of humour).

Klemm's Haymaking, also from 1906, finds him in another mood. This interest in people's livelihoods is just as close to Orlik as the more obvious japonisme. It's easy to forget the strong appeal of European naturalism to these artists and the way that the kind of realism they came across in Japanese art only served to bring things one step forward. Here is Klemm almost in popular print mode and he certainly didn't give up these descriptions of country people when he left Liboc; it's just that he has become better known for his clever and appealing animals in much the same way that Thiemann got himself stuck with birch trees.

But then that is in the nature of printmaking where you have multiple images. The two artists co-operated on two joint ventures, at least. I don't know the date of their Old Prague portfolio, or volume. I have only ever been able to track down one image that I can be fairly sure comes from this work. Klemm's rough-and-ready study of light and shadow in Empty Street I think must come from the work. I don't think I can be quite so sure about Thiemann's back street below. At least one rather unreliable source has it down as Lubeck. In a way, it doesn't matter because they certainly stand comparison. Possibly Thiemann never quite got the same cramped sense of narrative again. The washing, the steps, the washing-basket suggests the workaday life he had left behind in Karlsbad. He substitutes Klemm's seller of clothes for the lifeless washing; the open window is also there, but no source of light. The second project was a calendar for the year 1907. They would certainly have known the famous square calendar with contributions from members of the Vienna Secession, including Moser, made for the year 1904. They produced six images each for their own. This was reproduced in facsimile by Thiemann's widow after his death - one to look out for but a quick search turned up nothing so far. [I am am indebted to Klaus (who lives near to Dachau) for the information about the calendar, which I knew nothing about].

But the play of light is everywhere in Birches (1907(. [I couldn't find the auction-house image so I had to content myself with the Art Value lettering and their impudent copyright]. And with this print we come to the Carl Thiemann that everybody knows: the sense of pattern, the vigour, the stylishness. The play-off of the leaf shapes, the markings of the birch tree and the undisguised cutting to suggest the movement of the grass is already quite masterly. Compare this to the over-excited work of some Grosvenor School artists and you will see how simple-minded they actually were. And I think he also recognised his own success (or someone else saw this for him) because a year later his more famous image Birken im Herbst was being mechanically reproduced in Vienna. (I am also pretty certain that this grouping of trees would be known to Norbertine Bresslern Roth).

Normally, I would have edited the printed letters out but the handwritten display of Original Holzschnitt Handdruck 6/30 with central title and his full name says a great deal about his salesmanship. This was all part of the contemporary trend of distinguishing colour woodcut from the mechanics of C19th lithography and giving their work a personal feel. Although he describes the second print as an original colour woodcut, it is only signed in the block. There was nothing new about offering prints of different qulaity but this move into mechanical reproduction funnily enough precedes their own move to the long-established artists colony at Dachau near Munich. Klemm was to stay for only five years before moving on to the post of professor at Weimar; typically, Thiemann was to make the best of it - build himself and his family a house, and stay forever.

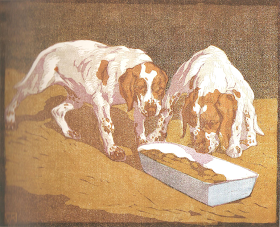

I includes Klemm's print of puppies at a bowl and Thiemann's early version of his swans as a postscript to their time together at Liboc. They may or may not have been produced there in 1908 but in some ways, it doesn't matter too much. Klemm proves himself to be the realist. The composition is almost wilfully inelegant. Ironically, Thiemann plays the Orlik game just as his friend had. In some respects, he is is less good at it than Klemm was. But in failing to connect with Orlik he finds his own voice.

Klemm's exquisite monochrome disquisitions on line and shape - his herons and flamingos that echo Ohara Koson - become a decorative little masterpiece in the hands of Thiemann. The bold arch of the neck and the flare of feathers behind sum up his peculiar intensity. It goes beyond the decorative formalities of the Secession to something delicate, impersonal, grave, unique.

it's so interesting to me how a small number of friends produced such lasting art. sometimes intentionally (by declaring themselves a movement or a workshop), or just by whatever magical frission happens when they get together. it's like a garden that has a few spots in which flowers grow profusely, and many more where little grows. in the garden it could be sunlight that makes the difference but the arts and crafts prove it's all just magic anyway.

ReplyDeletei really like that white/blue on that one image of birches, but most particularly i like that rooster up on top.

Yes, Lily, Zeus tempted Ganymede with a cockeral and I found that white cockeral equally hard to resist.

ReplyDeleteCharles

Orlik had a perfectly mature knowledge of where to put his colour and characters, to make motion, but Klemm and Thiemann too, knew how beautiful the power of lines well placed could be. There is no doubt that these artists knew their stuff. There are legitimate limitations due to the printmaking processes, but these three make them hard to spot.

ReplyDeleteOrlik's influence on Klemm is easy and apparent to see, and of course Klemm's influence on Bresslern Roth is easy to see as well. I see so much of the Munich school of art in the works of Klemm. The rather wonderful Turkey print with that very Munich matte finish was in the style favoured by the Munich printmakers of the 1900's. Moser of course was one of those matte finish printmaker masters and it's easy to see his influence in the works of both.

A keen and refined vision that omits the extraneous or busying aspects of a view show an incredible maturity but they also show a very Germanic aspect to printmaking but the works of Klemm, Thiemann and of course the master, Orlik trick us into thinking they are simple. I still think I want the turkey print, because it's just so bloody beautiful, dogs, cockerels and Middle Ages hamlets be damned!

Clive

Charles,

ReplyDeleteI thoroughly enjoyed reading your latest post! I didn't know Thiemann's "Birken", very interesting and obviously a forerunner of "Birken im Herbst". I think Klemm's best works by far are the "Silver Heron" and the "Flamingoes" that you mention in your post (produced much earlier than most of Koson's work, so Koson can't have been the inspiration, if you ask me).

Klemm and Thiemann also cooperated in publishing a calendar for the year of 1907. They took turns in conributing one woodcut for each month. A posthumous faksimile-edition was published by Thiemann's widow, Ottlilie Thiemann-Stoedtner.

Klaus

Very many thanks for the invaluable information about the 1907 calendar, Klaus. I have incorporated the details into the main text.

ReplyDeleteInteresting to hear that his wife outlived him. Do you know if she was his second wife? I must check the name of the person he married after he moved to Dachau.

Frankly, I would find it hard to believe Klemm didn't know of Koson's work even though he was only six years his senior. But you may be right about this. Something else to mug up on.

Charles

Charles,

ReplyDeleteI think you are right about Mrs Thiemann-Stoedtner having been his second wife, I vaguely remember reading that he lost his first wife and his daughter within a few years. I know a man in Dachau who lives in the street where the Thiemanns had their house (it is still there), he knew the widow and told me she was very active in keeping up her husband's memory even at a very old age.

As far as Koson is concerned: Apart from the fact that he produced most of his prints later than the "Flamingoes", for example, he doesn't use the monochrome black background as often as some other Japanese printmakers did. But you are certainly right about the Japanese influence: Klemm himself explicitly pointed out that by studying the Japanese he had learned to work out the essential in his birds.

Klaus

It's intriguing the way he persevered along those lines with his bird prints then gave up woodcut altogether.

ReplyDeleteAnyway, I have more intriguing Dachau/Klemm connections coming up this week.

Charles

I can't conclusively say that Orlik encouraged Klemm to enroll at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Vienna. However, Orlik returned from Japan in early 1901, not 1902. He was only in Japan for roughly 9 months, not 18 months, and left Japan in early January 1901. I'd have to check to confirm if he arrived back in Europe in January or February 1901, but if Klemm enrolled in 1901, it could have been at Orlik's suggestion.

ReplyDelete