Wednesday, 23 December 2015

Modern Printmakers update

I have reluctantly decided to restrict access to Modern Printmakers after some plagiarism. I'm not generally touchy about things like that; plagiarism is par for the course on the web but this was manipulative and sneaky.

This will mean that posts will be different - more of a fireside chat and with material I would have been reluctant to post publicly. I may well go back to public operations but I may not. In the mean time Happy Christmas to the happy few! I am off to Wales today so there will be no posts till later on in January at least. But I also have a trip to Turkey.

This year's Christmas cake is the V&A's proof of Ian Cheyne's wonderful Mediterranean Bar from 1935. I'm sure they won't mind just this once.

Friday, 6 November 2015

Ralph Mott

It is astonishing to find out just how much information has come up online in the past five years. In the early days of Modern Printmakers I wrote a rather crude and facetious post about the London sales promotion firm, Ralph & Mott, in the vain hope that someone would come up with information about the artists who worked for them. This week I was finally given two web addresses by a reader and decided to try and put together all the information and best images that are now available online.

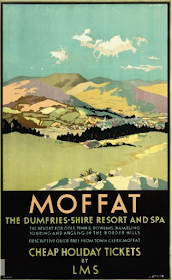

The business was set up I believe in the late twenties by Rickman Ralph and Geoffrey Mott at 46, Gillingham St, Eccleston Square, in well-to-do west London. The pair had already collaborated and the new business built on their success by taking a modern and efficient approach to all types of visual sales promotion. Inevitably, transport, travel and holidays provided a good deal of their work but the firm also designed information booklets like the one (above) for I.C.I.

As you see, there was no obvious house-style aside from a strong image with clear messages. Nor were they the most stylish of operators in the field, although their poster of Paignton gave G.W.R. as chic an image as any that might have been provided by Tom Purvis. But this was a sophisticated operation with a sophisticated address, employing artists who were well aware of contemporary styles and were able to project a modern image yet present a message that was understandable to the public. For the Radio Times, Edward MacKnight Kauffer was combined with an intriguing use of collage while G.W.R. were offered bold deco lettering and Paul Nash's soft surrealism.

But it is the simple repetition of the circular logo, the gold ball, the letters O and G and other letters and words that is striking. One of their selling points was that commissions were discussed 'in Committee' and what in fact they were offering companies was sales by way of both information and an image with a strong dose of modern psychology. I also need to add that Ralph Mott also produced artists prints which they signed in pencil. One showing part of old Sarajevo appears on the previous post about the firm and I seem to remember a flower print in the style of John Hall Thorpe. It may appear unscrupulous today but I suppose at the time people knew what they were buying.

As for their staff, in 1920 they took on Reginald Lander who became chief designer and head of studio. Lander had trained at Hammersmith School of Art and may be responsible for so many of the cool tones of the images because they tend to occur in his work for other companies after the war. He worked in watercolour and gouache and surprisingly a number of original designs from the studio using both mediums have survived. The only other artist I know of is Edna Reynolds who went by the name of Jenny Reyn ie Wren. She had trained at Wycombe Art School in Buckinghamshire while she was still at secondary after her headmistress recognised her talent. Like Lander she went to work for Ralph and Mott in 1930 but both artists lost their jobs after the outbreak of war when their employers decided to close the business 'for the duration' in an attempt to preserve their capital.

It is always possible I suppose when you look at the details of these images to tell they come from the 1930s. All the same what impresses me about so much of this work is how much it has in common with our own advertising. The clarity and simple division of lettering and images and use of basic colours is remarkably modern. No one style was allowed to come out on top and they were always full of ideas. Look no further than this poster for Buxton where three kinds of typography alone were used - clean modern deco for basic information, descriptive lettering for large appeal and Roman characters to add further interest and depth. Living not so far away, I know Buxton and find the image entrancing, but for readers who do not know the place, Buxton was a Roman town with natural springs, and St Anne's Well can befound at the bottom of the hill in front of the crescent you can see. Hence the figure pouring water from the vase. Its appeal is relaxing, stylish, erudite - and convincing.

- S P Q R -

I am indebted to various sources. Not surprisingly the invaluable National Railways Museum at York is one of them but I also have to include bearalley.blogspot, Liss Fine Art, the Science Museum, Quad Royal, The Travelling Art Gallery, halasbatchelor75, Moore-Gwyn Fine Art and frenesilivros.blogspot. Special thanks also to Peter for the leads.

Saturday, 31 October 2015

Carl Moser: castles of refinement

We have come to associate Tyrol with colour woodcut. Even if Engelbert Lap was born in Graz, he served with the Tyrolean Kaiserjaeger and settled in Innsbruck in 1910 and later made a career out of the mountainous landscape. Herbert Gurschner was born in Innsbruck and trained at the School of Applied Arts there but married an Englishwoman in 1924, lived in London from 1932 and eventually became a British national even though he remains best known of his prints of Tyrolean farming folk.

Carl Moser was different. He was not only more talented than either Lap or Gurschner, he was born in the Italian town of Bolzano many miles to the south. I say Italian because the town was predominantly Italian-speaking but was surrounded by mountains where most people spoke southern German except for townships to the east where others spoke the old romance language of Ladin - and it is Ladin that provides the key to the complicated nature of this Austrian Lebanon.; it was the old language of southern Tyrol. Italian and German speakers were more recent arrivals. But Moser isn't best known for Tyrolean subjects. Moser is best known for his Breton subjects. Unlike artists who came from regions like Alsace or the Sudetenland or even cities like Prague where German was spoken but eventually moved to Germany itself, Moser adopted another outlying province as an imaginative home, a sure sign of a sensitive and complex imagination.

The subject for his masterly Schloss Runkelstein is only a few miles to the north of Bolzano but by the time he made this colour woodcut in 1922, he had studied at the Academy of Fine Art in Munich and at the Academy Julian in Paris. Sources variously say he was introduced to colour woodcut in 1902 by Max Kurzweil or saw them exhibited at the National School of Fine Art. Either way nothing quite explains the utter refinement of his work. We can only look at it and wonder.

As you can see from the two versions of the print (and there is at least two others) Moser was a colourist. I certainly think the importance of Japanese art to Moser has been overdone. You only need to consider the way the castle sits squarely on its rock and the rock sits squarely beside the river or the peacock in Weissgefleckter Pfau (also from 1922) turns in space to see how much of a Western artist he was. What really is interesting is the way he looked back to the heyday of the Vienna Secession and made Weissgefleckter Pfau a self-conscious summary of its great achievements because it was certainly dead and buried by 1922. I think his imagination was historical. Japan was only another imaginative element in his work.

Look at the way he plays the modern world of silk hats and parasols off against the lace delicacy of the Breton bonnets. Audaciously, he even gives us two versions of the same figure in the one print. An archaic world fades away before our eyes. Folksy it may appear but the irony and the candid glance are modern. But it is the figure that is sensational. The woman on the right is just as solid as Schloss Runkelstein. Moser is not only concerned with surface pattern. The patterns help to describe form. More than that, as she looks over her shoulder, she reminds us of her ancestry. Manet is there, after all, and farther back, there is Goya perhaps, and certainly Vermeer.

Bretonische Hochzeit comes from 1906 while he was still studying and working in France. No doubt about it, he was an assiduous student and remained at the Academy Julian for six years when he was already capable of work as good as the wedding print and Bretonisches Dorf von Schiff aus (1904). He had begun to learn his trade early on in his father's studio and there is a sense of the studio in the foreground boat with the secondary image acting as subject. The framing devices and the ornate pile of rope are obviously Japanese. But it is the sense of space that he has picked up from Hokusai that is more profound, perhaps even the delicate psychology.

Moser was as tactful in his observation as he was in his use of colour and his borrowings from other artists, close to hand and far away. But he was a rather half-hearted symbolist. Pelikan is just too real to be a lot more than an ironic enquiry into ungainliness by an artist who was incapable of such a thing. But let's face it, the drawing and the colouring, the realisation of the pelican's body are superb. All the rest is froth, isn't it?

Wednesday, 28 October 2015

Classic colour woodcuts on ebay from Austria and Germany

Christmas has come to ebay in Austria and Germany with an astonishing review of early C20th of colour woodcut, and with nothing more striking than Hans Frank's exquisite tour-de-force Schwartzlilien from 1940. But I warn you, before you go rushing to put in a bid for some of these celebrated prints, the most collectable ones start out at a breath-taking 1200 euros. Included amongst these is a desirable In Ertwartung by the Austrian artist and designer Carl Moser from 1914 (below).

There are two things that strike me here. What always impresses me about the market in Austria and Germany is how much is still available after 100 years and how much you need to pay for them despite there being so many of them (relative to the British market, at least). If nothing else, it says a good deal about the good sense of collectors in both countries. So far as I can see neither Germany nor Austria have John Hall Thorpes and Eric Slaters where people are prepared to pay £1200 (in the case of Slater) for work that cannot begin to compare to the prints you see here. Of course there are Anglophiles in Germany who like to buy English prints, Slater included, but not at that price.

But not everything is expensive and Walter Helfenbein's Zwei Prachtfinken (above) should fit under the Christmas tree without making too large a hole in your bank account and is also well worth having. But then much the same could be said for Carl Thiemann's Birken im Herbst. Made in 1907, it comes from the period when Thiemann was using brighter colours and a more decorative approach to printmaking in general. It also has the great advantage of being from the signed edition. (Others were printed on a mechanical press).

Also from the signed edition is Walther Klemm's well known print Junge Hunde. More out of the way is something very nice by Christian Ludwig Martin. Beautifully made and very pleasing, Boehmerwald dates from 1917 and looks back both to the days of the Vienna Secession and forwards to more popular work of the post-war years. It may not make the pulse race but it will leave you enough to spend on Christmas dinner.

Never really an artist to have much appeal for me and certainly not in the top rank, Leo Frank's Adler im Hochgebirge has all the emptiness of his twin brother at his weakest but with none of the decorative thrill when he is at his best. It's quite acceptable nevertheless as part of the general festive generosity.

Friday, 23 October 2015

Emil Orlik and a Colnaghi wash mount on ebay

This is something by way of a public service announcement. I certainly don't think the dealer who currently has the Emil Orlik portrait etching for sale on British ebay deserves it. But take a look at the wash-mount round the etching, which the seller thinks needs replacing. This is certainly the type of mount that was used by the Bond St dealer Colnaghi before the first war and as such I think needs looking after and not destroying. Instinct told me to preserve a similar mount round a Verpilleux colour woodcut even though my framer wanted to replace it with the same kind of thing. It was only years later I discovered that Colnaghi had them made. Not very important perhaps and obviously I cannot be certain about this particular mount but I also own a portrait etching by William Strang with exactly the same kind of mount. What's not to like? I haven't checked to see whether Colnaghi was also Strang's dealer, and it hardly matters. What I am saying is this: apply caution when dealing with nice old mounts. They have history, too, and may be worth restoring not chucking out.

Saturday, 17 October 2015

Edinburgh School

The one thing I did not want to do in the last post was to give the wrong impression about Mabel Royds herself. I suspect the reason she was willing to help Norman Bassett Hall was because she had always learned from other artists throughout her own working life. But then there are so many misconceptions about Royds, it is hard to know where to begin. But one person that was right about her was Malcolm Salaman when he described her work as synthetic. It was not only a matter of how much she assimilated from other artist, there was also something premeditated about her use of colour.

The Indian notebooks are also misleading. It has also struck me as odd that notebooks that were sometimes ten or more years old could provide the basis for new work. But you only need to compare Elizabeth York Brunton's colour woodcut 'The pergola' from 1922 and Royd's 'The musicians' from 1927 to see how far Royds could synthesise her drawings made in India and work made by her contemporaries after she had returned.

Royds and her husband had moved back to Edinburgh in 1919 while York Brunton had been born there and had trained at Edinburgh College of Art amongst other places (but almost certainly before it became a college under Frank Morley Fletcher in 1907). Like Royds (who was six years older) she had also trained in Paris and had spent time working there. She was a sculptor-printmaker like Eric Gill and to a lesser extent Robert Gibbings. She had a strong interest in structure, texture and light. Her prints are far from technically perfect and often have a scrappy look to them but they were also spontaneous and exploratory and again I suspect this was what attracted Royds who after all was quite a literary and cerebral artist. But then York Brunton was no slouch herself when it came to lifting ideas from others. Take a look at William Giles' 'At eventide, Rothenburg am Tauber' from about 1905.

Giles had a wayward originality and commitment to his trade that was beyond the reach of many artists and York Brunton's inclusion of his outlandish orange rooftops in her own print shows exactly the kind of example he had set for artists who were making colour prints. His work is seminal, it is as simple as that. I had always assumed that York Brunton had used a French subject for her print. Looking at the all together for the first time, I can't really avoid the coming to the conclusion that her woodcut shows Rothenburg as well! She did work in Germany as well, after all. What is fascinating is the way the combination of deviant purple and warm sand was first transferred by York Brunton into her own woodcut then taken up by Royds along with Brunton's use of shadow.

All this strikes me as productive and not at all inbred. All three prints have something different to offer us. York Brunton's may be the weakest but it also has the kind of nonchalance and vigour we have come to expect from good modern prints. Royds' woodcut was masterly in a more obvious way. The use of western conventions - the sense of light and space and the study of the human figure - are plainly obvious. Less apparent is the subtle use of double framing to enhance the intimacy of the scene and her constant sense of crowded space was perhaps never bettered than it was here. Giles' print is of course superb printmaking. No British artist, before or since, did it quite like him. Beyond that, the imagination was at work. It's those quirky white railings that give away how fascinated he was by what he saw but the way he re-imagined those things. If Royds synthesised then as someone once said about Giles, he transposes his feelings.

Saturday, 10 October 2015

The road to the isles: Norma Bassett Hall in the Highlands

Colour woodcut is more of an industry in Germany and the United States than it is here in Britain (where it remains in the shadow of the modish contrivances of the Grosvenor School). This even comes out on Modern Printmakers which now has fewer British readers than American and German ones. There have been a fair number of books published in the US, mainly about individual artists, including William Seltzer Rice, Walter Phillips, Edna Boies Hopkins and Arthur Wesley Dow. Alongside this there are learned articles by Nancy Green from Harvard. All to the good but lacking in any real knowledge of what was happening in Europe, surprising because a number of these Canadian and American artists became friends of British artists and Boies Hopkins even visited Britain before the first war. But what do American scholars know about that?

The Halls arrived in Glasgow in June, 1925, and went over to meet the Lumsdens in Edinburgh. Then in August, they went on a trip to Skye by way of Crianlarich. Apparently while on Skye they stayed for about a week at Portree and then over a number of years, Hall made four colour woodcuts of Highland scenes, including Portree Bay (top) and A croft at Crianlarich (1929 - 1930). Unfortunately, I can't seem to find an image of A croft at Crianlarich and the one above is Cottage on Skye which she made as late as 1940. But it was Gerrie who discovered that Rice had made a woodcut called Aberfoyle, Scotland and, as it happens, Aberfoyle and Crianlarich are only about twenty miles or so from one another.

Hall was a magpie. You only need to look at the work Helen Stevenson was doing by the time Hall visited Scotland, especially The hen wife (1924) to see where some of Hall's ideas for A Highland Croft (1927-1928) came from. Not only that, there are some obvious similarities between Hall's print and Kenneth Broad's A Sussex Farm (1925) exhibited at Los Angeles in February, 1926. But her borrowing worked because the colour woodcuts she made in the States based on the trip to Scotland are the best things she ever did, certainly a lot more lively than the woodcuts that drew their inspiration from trips to France. Hall was a rather repetitive and unoriginal artist as you can see from the basic sameness of the buildings and their similarities to the work of Rice (who had cabin-fever) but as an American she could ignore the British conception of things and made the Highlands look like a cross between the Rocky Mountains and Pont Aven. OK, it's easy enough for a European like myself to snigger but by comparison, Rice looks merely craftsmanlike. The question is, though, was he there as well?

Friday, 11 September 2015

The 1890s & experiment

In July, 1899, the London gallery of Goupil held an exhibition of work called Original etchings printed in colours by Theodore Roussel, a title that could hardly have prepared visitors for the nine sensational objects that made up the show. 'Original' was hardly the word for them. Chic, waywardly exquisite, outlandish, and of these terms might have served better but 'original' it was because from beginning to end, Roussel had made these unbelievable objects in his studio at Parson's Green.

Roussel was of course French. You had to be to make anything so weirdly devastating. And though I laugh, I have to say I have warmed to Roussel and what he was doing. Untrained, he was nevertheless a fine painter, who had been introduced to the art of etching by the American J.M. Whistler but by the nineties had come well and truly out of Whistler's shadow. Call it zeitgeist, call it originality, somewhere along the way Roussel had hit on the idea of mounting and framing small colour etchings showing vases of flowers and views of Chelsea in the most refine and unusual way. To be honest, I am vague about the techniques he used but they were complex and required numerous printings. Decadent they may seem ay first view but radical is hardly the word. But why?

Untill then, the proper home for a print was a portfolio or solander box and every single one of them would have been in black and white as Rembrandt's and Mantegna's had been and as Whistler's were. All right they were exceptions, notably Italian chiaroscuro woodcuts but intaglio prints were another matter. Beyond that by offering his prints for sale - ready mounted and framed would be an understatement - Roussel was exhibiting his conviction that they belonged ion the wall along with the oil paintings and what have you.

Here were two radical departures and yet there is a third aspect to all this that not even curators at the V&A with all their erudition will point out to you. These object were crafted. There were no editions, each one was unique, a very different approach to the one we take today in deciding upon the originality of prints. It was not unusual by then for artists to blur the differences between the fine arts and the production of a series of objects. One look at the enamel work of his contemporary, Alexander Fisher (above) should make that obvious. But no one had had the sheer temerity to approach a print in this way.

Interestingly enough, Fisher had had to go to Limoges to discover for himself the old ways of making fine enamel. Back in London he had gone into production and was making work like Glad tidings and Cinderella and the doves by 1898. By that point he had been teaching the art of enamelling for two years at the Central School of Arts and Crafts where at least one student was the printmaker, Ethel Kirkpatrick who would also have been taking Frank Morley Fletcher's class in colour woodcut by 1897. Unfortunately, despite trying, I have still been unable to track down a single image of Kirkpatrick's jewellery (and believe me I have been at it for years) so you must make do with work produced by Fisher's follower and assistant on the class, Nelson Dawson, who worked alongside his wife, Edith.

The Dawson's took the Morris approach to production, dividing up the tasks between themselves and their craftsman, with Nelson acting as designer and Edith head enameller. Boldly attractive and colourful, with none of the detachment of Roussel or the religious symbolism of Fisher. They were highly successful and their work much sought after for a number of years. They also make plain what they had in common with their contemporaries like William Giles (below).

Bear in mind that Giles was the son of a craftsman and describing himself and his fellow practitioners as an art worker rather than an artist. How Roussel saw himself is another matter. Nevertheless when a group of artists making colour prints in Britain had their first proper meeting (the true date has never really been ascertained but it by 1910) it was held at Roussel's house in Parsons Green and Roussel himself became the first president, a post he held until his death in 1926 when Giles took over. Looking back at it, it was an appointment that seemed hard to understand. By 1910 colour etching as a fine form in Britain had had its day. But Roussel was French and the kind of colour woodcuts that Seaby and Fletcher were making had already peaked and gone out of fashion in France. Meanwhile the Dawsons (bottom image) the Lee Hankeys and the Austen Browns all had studios in or near Etaples

Well before then Giles had taken his lead not so much from Fletcher as from Roussel, producing work like Midsummer night that was as refined as anything Roussel had made and equally ignoring the rules in order to make something startlingly original. I have to admit I have moved about seven or eight years away from the nineties but it shows the extent to which it was Giles who tried to hold the course by making colour prints by the best means possible and not trying to divert the enterprise along the more conventional Japanese course. I saw the face of one of those curators at the V&A when he had this print in front of him for the first time, astonished that anything so fine could have escaped his notice. Believe me, nothing prepares you for the sheer craftsman-like magnificence.

Placed in this kind of context, a print like John Dickson Batten's The centaur starts to make more sense, sense that becomes more interesting once one compares the work that John and Mary Batten later produced for St Martin, Kensal Rise in London and the triptych made by Fisher (above). Also bear in mind that Mary Batten was a carver and gilder like Giles' father and it all begins to make even more sense still.

Wednesday, 9 September 2015

A Studio lithograph on ebay: John Dickson Batten's 'The tiger'

John Dickson Batten is having his day. Within only days of two postings about him (on Modern Printmakers and on The Linosaurus) here we have another Studio lithograph of one of his prints, this time his first original print called The tiger. I hasten to add that what you see above is an original proof owned by the British Museum and donated by Batten himself in 1920. Below is the lithograph that has just been passed over on British ebay. (It was up at the OK price of £3.50). But no doubt you can tell the difference.

First the story. Batten worked with Frank Morley Fletcher on two colour woodcuts then made this print in Fletcher's first class at the Central School of Arts and Crafts 1897/1898. I don't know whether Batten ever said in print why he allowed lithographs to made of his early prints. He did say that what he wanted to with colour woodcut was to avoid mechanical means of reproduction and I assume the reason behind The Studio publishing images of both Eve and the serpent and The tiger was to gain extra publicity for the whole colour woodcut project and not to pass them off as original prints. They are reproductions and nothing like the lithographs being produced by Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon at the time.

Would I buy one? No I would not. I did once buy a lithographic reproduction of a watercolour by Arthur Rigden Read on ebay and I treasure it because it is a fine example of the technique of lithography by Read's fellow students and adds a good deal to the little I knew about Read's early career but I paid only a few pounds for it. And it's what ebay can do well - allowing people to exercise their eye and to make use of what they know to pick up something interesting for a few quid. Going on about what some Studio lithograph might be worth takes the excitement out of everything.

Monday, 7 September 2015

Charles Bartlett at the Academy Julian, Paris, 1887/1888

It might seem a bit odd to pick out Charles Bartlett from such an illustrious group of young artists at the Academy Julian in Paris but it continues a conversation between Darrel Karl at Eastern Impressions and myself about students who attended the Paris academies in the mid 1880s. Some of this has been by email, which doesn't draw in others. So here for the first time for me at least is the first photograph I have seen of a young British colour woodcut artist. (He was 27 or 28 at the time). He is un-missable on the left, with his arm stretched out above the easel.

I will just pick out four others. Paul Gaugin is right at the top and rather out of focus. The man with the delicate features and in a light waistcoat below Gaugin is Vincent van Gogh. To the back of him, with equally fine features and watch chain is Pierre Bonnard. Less well-known is the Scots artist, A.S. Hartrick, front centre with the handsome moustache and hand rested on the shoulder of his companion. (He was a friend both of Van Gogh and Frank Morley Fletcher who attended the academy soon afterwards.) Other British colour woodcut artists-to-be who attended were Ethel Kirkpatrick and Elizabeth Christie Austen Brown who also became a neighbour of Bartlett's back in London - and long-term readers of the blog will know just how much I would like to find a photograph of either of them.

And before anyone thinks that the research is mine, the photograph and identification of the artists can be found on a Van Gogh post on the library blog at L'institut national d'histoire de l'art or INHA. I was hazy about how to get the link working, I'm afraid.

Sunday, 6 September 2015

John Dickson Batten's 'Eve and the serpent', 1895

There has been some discussion over at The Linosaurus about John Dickson Batten's well-known colour woodcut, 'Eve and the serpent' and also the mechanical reproduction of it published by The Studio in February, 1896. This is the best documented of all British colour woodcuts with all the documentation available somewhere online and I have to say I think it is surprising that so many errors keep on resurfacing about this particular print. Both the British Museum and the Hunterian at Glasgow agree that the correct date is 1895, basically because that is what Batten said.

The image at the top is readily available online and shows the proof from the collection of the Hunterian and is annotated by Batten as number 42. Obviously quite a few were printed, all of them, it would appear, by Frank Morley Fletcher - certainly this one was. Batten said that after a period of experimentation Fletcher found that using Japanese technique provided the most satisfactory results. Even so, the Hunterian point out that one of the six blocks was made of metal. This was the same approach adopted by George Baxter earlier in the C19th. It was not until Batten and Fletcher made a second print together that Fletcher adopted a pure Japanese manner and with the keyblock closer to ukiyo-e prints rather than the Kelmscott Press type of woodcut.

Japanese method or no, Batten's models for the print were purely British. Compare The Forest, the very subtle tapestry designed by William Morris, Phillip Webb and John Henry Dearle in 1887. By 1895, the year that Batten and Fletcher worked on 'Eve', Dearle was chief designer at Morris and Co was responsible for a lot of the foliage and flowers in the background of tapestry and stained glass designed by Edward Burne Jones, another obvious model. It is less obvious perhaps, but what also attracted Batten was the co-operative manner of work at Morris and Co. He was not the type of man to roll up his sleeves and have a go like Morris who tried everything from vegetable dying to glass-blowing and it was not until Fletcher began taking a class in woodcut at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in 1897 that Batten learned how to make a colour woodcut but he was keen to work with others when developing new methods of work.

It has been noted that his second oil painting, The Garden of Adonis - Amoretta and Time (1887) used a series of glazes laid over pure colour in true Pre-Raphaelite fashion. What he wanted to achieve with woodcut was perhaps similar, some way to print in opaque colour without using the mechanical means employed by people like Baxter. This is exactly why not too much value should be placed on The Studio image. It was there to draw attention to the making of a colour woodcut that Batten had been reporting on for some months before he and Fletcher had any idea they could make the project work. Again it was an open-ended and co-operative effort and quite remarkable for that and the beginning of what Fletcher went on to call 'the movement'.

Tuesday, 1 September 2015

Kenneth Broad's 'A Sussex Farm' revisited

To my surprise the American seller of this woodcut did the sensible thing and re-posted it on a proper auction basis. It currently stands at just under £100 with less than four days to run but it won't stay there. That said it will be interesting to see what does happen. It may have blemishes but this is Broad at his best. The colours are especially fresh and vibrant, the image beautiful.

By way of added interest I am also posting his masterpiece, 'New Fair, Mitcham' which I believe was also completed in the autumn of 1925 and acts as a companion piece. Both subjects are summer-time scenes but astonishingly Broad chose to depict the fair in red and grey. Almost as surprisingly Broad failed to enter the print for the California Printmakers Exhibition in February, 1926, and entered a 'A Sussex Farm' instead. I think he may well have stood a chance of winning even against Rigden Read's very fine 'Carcassonne'. But then Read thought 'Carcassonne was the weaker of the two prints that he had accepted so it shows that neither artist was a good judge of their own work.

Tuesday, 18 August 2015

John Dickson Batten and the hobyahs

Striking, really, that he should turn to Hokusai when he was need of protean figures. Hokusai had both humour and creativity in abundance. Striking, too, just how much Batten put his own mark on his hobyahs. An admirer of Japanese art, he had no real use for Japanese aesthetics and believed Western artists had to adapt what they had learned from it.

Not surprising if you consider how far his professor at the Slade was steeped in the Western tradition, the kind of man whose idea of what to do on a trip to Italy was copying frescoes by Raphael in the Vatican. You can how much he learned from the Old Masters in the drawing a Greek man.